▶The original article in Japanese can be accessed here.

“Requesting refugee application, Requesting accommodation”

“〇X Guest House – Accommodation 8/2-5, request for food”

“Hotel 〇X – checking out today, need to arrange internet cafe”

This is a sample of memos taken from the Japan Association for Refugees (JAR) consultation list. Every day at JAR, we receive a variety of enquiries from refugees who have fled from about 70 countries around the world. It is not just a case of “I am a refugee and I need help.” Many come to us stating “I have no place to stay and need food”, as they battle serious health issues and face life-threatening problems.

Through our support activities1, JAR has seen poverty levels of refugees coming to Japan getting worse year by year due in part to the rapid increase in the number of refugee applicants since the 2010s. The number of new visitors to Japan dropped sharply in 2020 due to the spread of COVID-19, but the situation has changed rapidly with the relaxation of immigration restrictions from the fall of 2022. During this period approximately 600 people visited the JAR office each month.

JAR is currently providing services on the verge of exceeding our capacities.With collaboration and consultation with other organizations who assist refugees in Japan, religious groups, and organizations for people in need, we are doing our utmost to ensure the survival and livelihood of refugee applicants. Help from citizens to support refugees as if they were their friends and neighbors is also crucial.

Despite being forced to flee their homes to protect their very own lives, why do they now face this situation? In this article, we will discuss the right to life (the right to live a life with at least the minimum level of health and culture) of refugee applicants, and the current situation and issues surrounding the public assistance (hogo-hi) for refugee applicants.

Refugees are people who have been forced to flee their homelands due to conflict or human rights violations. Their lives are turned upside down and many of them are separated from their families and loved ones. On top of that, they would arrive in Japan not knowing anyone and with no understanding of the language. They simply arrive in Japan because this was the country that provided a visa easily, with only the knowledge that it is a developed and safe country. Most refugees flee without knowing the difficulties that await them. They must face the reality of not having food, clothing, or shelter, and it pushes many refugees into a state of mental stress. As you read on, we encourage you to imagine yourself in their shoes living day-to-day with no end in sight.

Though the rights and social security of refugee applicants may vary from country to country, Japan lags far behind other countries. And with the lack of public support funding, the right to life is virtually not guaranteed. The current situation in Japan is dire. We hope this article provides an opportunity to think about what Japan should be aiming for, especially as a member of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and as a member of the international community, and Japan’s responsibility in addressing refugee issues.

目次 [閉じる]

1. What is the public assistance (hogo-hi) for refugee applicants?

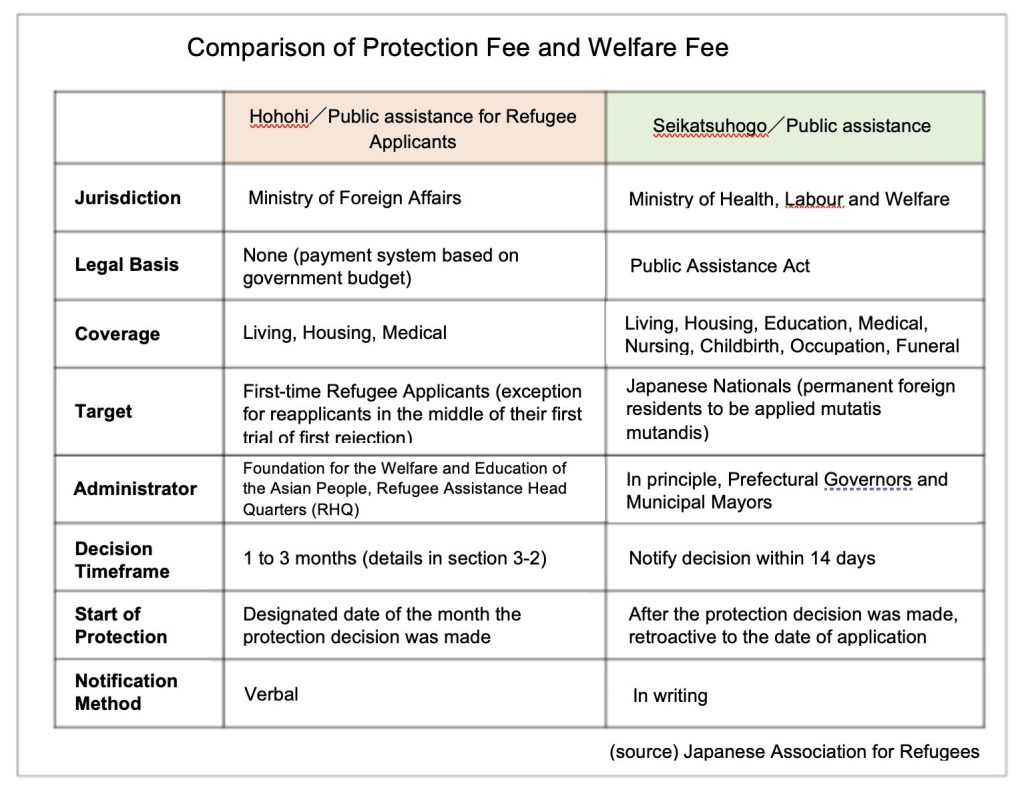

Public assistance2 by the government for refugee applicants found to be in poverty (protective measures for refugee applicants, hereafter referred to as “hogo-hi”) was first established in 1981 when Japan acceded to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees upon accepting Indo-Chinese refugees. As a result, implementation began in 1983. This work is carried out by the Refugee Assistance Headquarters (RHQ) of the Asian Welfare Education Foundation under contract from the government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

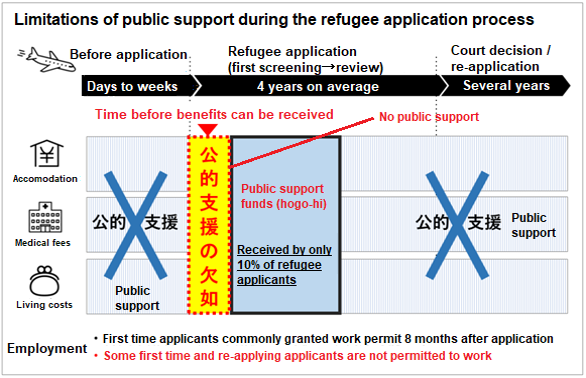

The hogo-hi includes living expenses (1,600 yen/day, 1,200 yen/day for children under 12 years old), housing expenses (single person: 60,000 yen/month, family of 4: 80,000 yen/month), and medical expenses (payment up front). It is the only public assistance and safety net for refugee applicants who have just arrived in Japan without work permits or housing and are in dire straits. However, as shown in the diagram above, the waiting period for payment of funds is long (see 3-2 for details) and leads to some people becoming homeless during that time.

The condition is that refugee applicants are expected to work and support themselves until the result of the application is announced3. Therefore, the hogo-hi is considered to be provided only for the limited period from arrival in Japan until work status is granted4. Given the fact that the process for refugee recognition takes several years, (on average, just under four years, as of 20225), most people look for work to feed themselves once they receive a work permit. We hear from many refugee applicants that they would like to work and become independent rather than relying on aid. However, even if one obtains a work permit, it is not easy to find work due to the language and cultural barriers. Furthermore, finding employment is even more difficult for vulnerable people, such as those who have been traumatized by experiences of persecution, single-parent households, and single minors. It is therefore necessary to continue providing benefits to people who find it difficult to work.

This situation changed significantly with the partial amendment of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act in 20186. Notably, some first-time applicants and most applicants who are re-applying for refugees will no longer be granted a status of residence, and that they will no longer be able to work. These rights had previously been granted automatically.

The government (Ministry of Justice) claimed it was to “curb abuse and misuse of applications for refugee recognition”. However, the reality was that the crucial enhancement in the legal systems to recognize those refuges who ought to be protected was neglected and instead, the regulation and exclusion of such people were put in place. The effects of such changes further continue to threaten the survival of refugee applicants today.

2. The relationship between Foreigners and Human Rights

Before getting into the main topic, let’s look at the relationship between human rights and foreigners (foreign nationals)7)

For us to live a normal life with peace of mind, it is important for human rights to be guaranteed. Human rights are not a concept that comes with “obligations”. Human rights are fundamental rights that everyone is born with, and they cannot be deprived. The state has a responsibility to guarantee this. In Japan however, the seriousness of the deaths and destitution of foreign nationals in detention facilities run by the Immigration Services Agency (ISA) is commonly downplayed. We often hear people say things such as, “I feel sorry for them, but it can’t be helped,” “They had no status of residence, so it was their own fault” or “Japan doesn’t have the capacity to help foreign nationals.”

Out of all human rights, the right to life is an important and essential right for humans to live as human beings. Nevertheless is better, along with the right to vote, the right to life is sometimes said to be one of the human rights that is not guaranteed to foreigners. This is rooted in the idea that the responsibility to guarantee a person’s right to life lies with the nation to which he or she belongs.

The reality is that there are people whose country of nationality is not the country where they live (long-term foreign residents), people who are not a national of any country (stateless persons), and people who have been driven out of their country of nationality and cannot return (refugees). In line with this, within international law (the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Human Rights), the idea that the right to life is not necessarily tied to nationality and should be guaranteed to all members of society, is becoming mainstream. In recent years, guarantee of the right to life is increasingly considered to be the obligation of the state8.

3. Issues with the public assistance (hogo-hi)

The challenges of the public support fund, or protection fees, include: 1) lack of legal basis, 2) a lengthy waiting period to receive benefits, 3) insufficient benefit allowance, 4) only a few are eligible to receive benefits, 5) overwhelming lack of housing support and 6) differences between nationalities. These will be explained individually below.

3-1 Lack of Legal Basis

The first major issue is the lack of legal basis (grounding law) for the livelihood protection of refugee applicants.The provision of protection fees started a year after Japan joined the Refugee Convention in 1981, given the fact the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) was advised an administrative improvement9 (administrative audit). In other words, administrative measures have been taken without legal basis for the provision of protection fees.

Let us compare the issue of lack of legal basis against the Public Assistance Act which regulates livelihood protection. The Public Assistance Act stipulates that applicants must be notified of their eligibility “within 14 days of the date the application is filed”. Although there is still a serious issue that people in need are not receiving enough welfare, it is important to have a law that secures a fair and transparent procedure and guarantees rights.

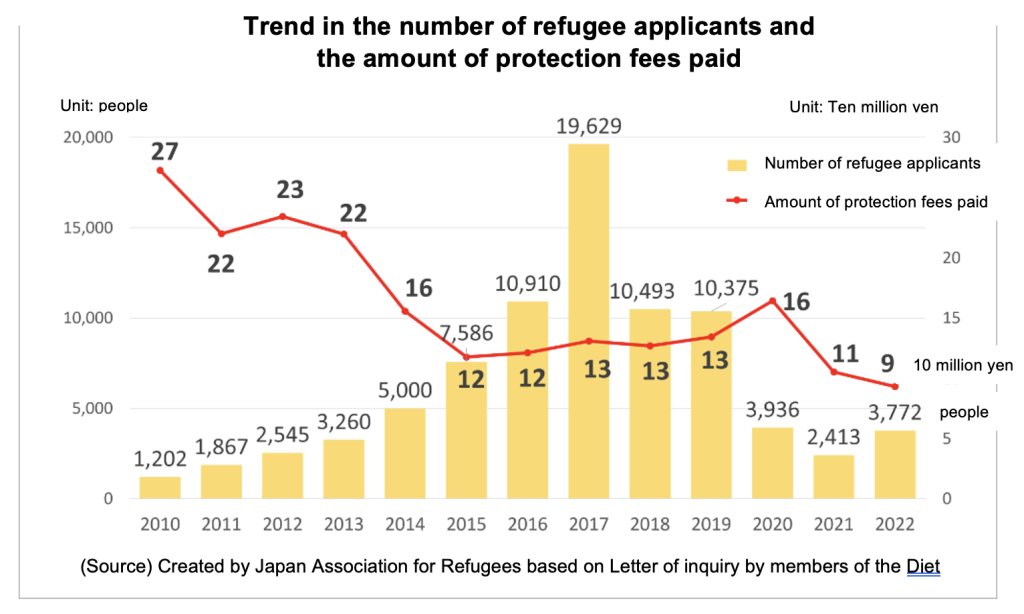

The number of refugee applicants fluctuates each year, influenced by international circumstances and immigration control policies of each country. It is necessary to establish a mechanism that allows to adjust the protection fee budget, in line with the fluctuation of refugee applicant numbers, that can quickly respond to any changes in the field. In the past (2009), many of the refugee applicants were neglected and dismissed without any vital support, as provisions were discontinued due to the exhaustion of the protection fee budget10. In addition, delays in the protection fee process have become common, some taking more than 6 months. It is essential to have a legal basis that secures the “Protection Fee” for refugee applicants to avoid these issues.

Furthermore, refugee applicants do not possess the right to appeal (request for review) for their protection fee procedure. Normally, the right is granted by the Administrative Complaint Review Act, however as the protection fee is not a refugee (foreigner) right but an administrative measure (action taken at the discretion of the government), the Administrative Complaint Review Act does not apply. Even for the livelihood protection system, which does have a legal basis, foreign nationals are treated as quasi-citizens (based on the idea that foreign nationals are not applicable as they are not “citizens” but may receive livelihood protection as a mutatis mutandis benefit) and are not eligible for appeal11.

3-2 Long waiting period before receiving benefits

Although refugee applicants are in desperate need to survive one day at a time, it takes many months to receive benefits after applying for the protection fee. As the above chart12 shows, there is a long waiting period to receive benefits, and the reality is even worse. The waiting period indicates “the period of time between when RHQ receives the application for protection fee before confirming with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and when RHQ receives back a notice on the decision of the provision”. This is the “Published Waiting Period” as mentioned in the diagram below.

In actuality, the process takes several to six months (“Actual Waiting Period” in the diagram below). For example, JAR has confirmed frequent cases where a refugee applicant would call RHQ to apply for the protection fee after filing the refugee status application, and would be told to “call again after 3 weeks”. As a result, there have been cases where the waiting period took as long as 7 months (as of September 2023).

We assume that RHQ may not have enough manpower to respond quickly, or it may take time to arrange translators which leads to delay in the provision of protection fees. However, we believe that having a law in place would allow the government to establish a system that could adapt to any situation. Unfortunately, coupled with the fact that there is no legal basis at this moment, the circumstance of the protection fee provider (MOFA and RHQ) takes precedence over the needs of the refugee applicants, resulting in procedural delays that are not being remedied sufficiently.

3-3 Insufficient allowance

The living allowance is around 48,000 yen per month for a single household, and 168,000 yen for a family of four (with 2 children)13. Housing allowance is maximum 60,000 yen for a single household, and maximum 80,000 yen for a family of four14. A rent agreement must be signed under the refugee applicant’s name, and there is no provision of deposit or key money. The amount is also small, being about two-thirds (in Tokyo region) of the welfare benefit which “guarantees the minimum level of living”.

The cost for appliances and household goods to start a living from scratch in Japan, including bedding, cost of children’s education, cost for refugee application (transportation fee to visit the immigration bureau, renewal of residence status etc.) will all need to be paid out of this protection fee. Given the recent rise in the cost of living and utility bills, refugee applicants’ lives have become even more challenging. In addition, medical expenses are provided through reimbursement. Therefore, people who do not have cash may refrain from seeing a doctor and worsen their symptoms.

Additionally, even though it is difficult to make a bare minimum living out of the protection fee, the government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) does not accept other incomes other than the protection fee in principle. In other words, benefits (childcare allowance etc.) that may be available to refugee applicants are considered an income in many cases, and will be deducted from their protection fees. Many try to make ends meet by cutting back on food expenses, perhaps by only eating once a day or refrain from going out as they cannot afford transportation expenses, and make sure they do not run out of cash until the next provision of the protection fee. The amount of fee itself is not enough to maintain a minimum level of living, and refugee applicants cannot escape from their bare minimum life unless the government allows other forms of income or increases the benefit amount.

3-4 Only some people can receive the benefits

Despite being the only public assistance for refugee applicants to support their livelihood, since 2010, in principle, only first-time refugee applicants are eligible to receive protection fees15. Japan’s refugee recognition system has many issues, and within those who have been granted refugee status, approximately only 7% are those who are approved after reapplication16. This means, while there are systemic issues leaving people with no choice but to reapply, restricting the acceptance of re-applicants poses a serious problem. It would have been sufficient if they could obtain authorization for employment instead; however, there are refugee applicants who are not allowed to work and restricted on the status of residence necessary to reside legally, depriving them of all means of survival.

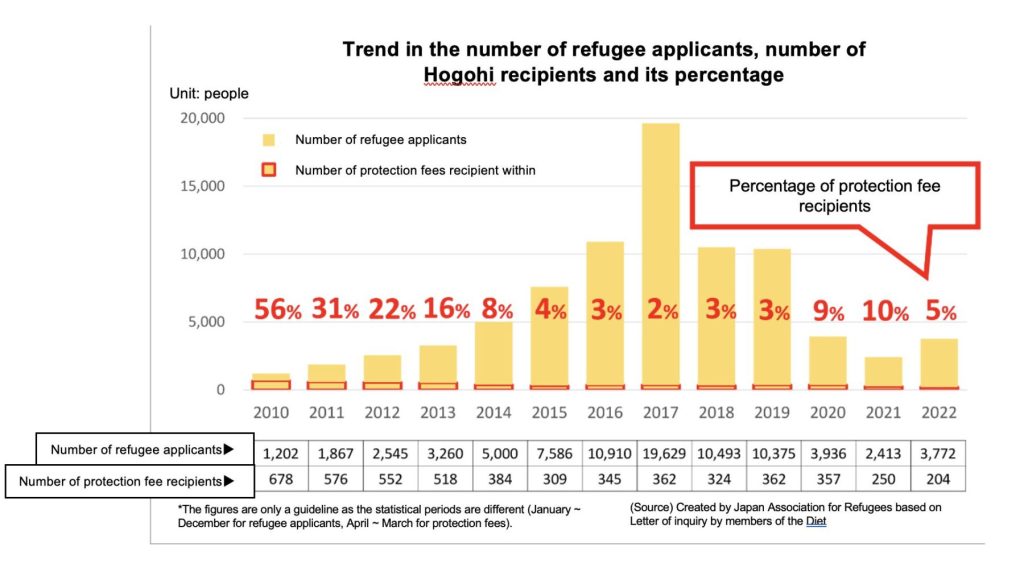

Next, let’s look at how many people received the protection fees. As the second graph below shows, in recent years, the number of people receiving protection fees have remained less than 10% of the annual number of refugee applicants17.

In reality, many people who applied for protection benefits to RHQ are able to receive them18. Looking at this alone, it can be said that most of the needs are being fulfilled, but JAR believes that many people are not even aware of the information about protection fees in the first place, and such benefits are not provided to the people who need it. No information is provided from the Immigration Bureau when submitting a refugee application, and it is difficult to access the information unless connected with a support organization like JAR. In fact, most of JAR’s clients need protection fees, and they are applying for them.

Furthermore, JAR is unable grasp the whole picture of refugee applicant living conditions. We are only able to assume that those who are not eligible for or unable to receive protection fees are managing to survive each day though the support from fellow citizens residing in Japan, or from communities connected through religion, or from individuals they have encountered in Japan.

3-5 Overwhelmingly insufficient housing support

Housing is essential to maintain a basic standard of living. The government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) began to provide shelters (emergency basic accommodation facilities) to refugee applicants in 2003, and has in place, a system for people who urgently require housing. This shelter, commonly known as ESFRA (Emergency Shelter for Refugee Applicants)19, is arranged by RHQ, who evaluates the urgency among those eligible for protection benefits. Even if there are personal needs, it is not possible to apply on your own. It also does not necessarily target those who are highly vulnerable, such as single-mother households, and the objective criteria for admission is unclear.

Furthermore, as the graph above shows, the number of ESFRA provided has been extremely small throughout the years, and despite having a system in place, it has not been provided to the people who need it. There is also a lack in quick responses, even though urgent arrangements are required. When ESFRA first started in 2003, it was operated on the principle that moving in on the same day is possible, if there was an emergency20. In addition, according to the actual results, ESFRA was provided to a certain extent during the first half of the 2010s (2010 = 41 people, 2011 = 48 people, 2012 = 24 people)21. However, since 2013, the number has dropped to where there was no provision at one point. In 2022, RHQ provided ESFRA to 25 people while JAR provided it to 223 people, which is 10 times more than the previous year. It is very clear that the private organizations are taking over the responsibility of ensuring a safety net for refugee applicants, which should be the responsibility of the government.

3-6 Differences between nationalities

Finally, we will explain about an issue regarding the lack of fairness in treatment among different nationals.

In addition to those who came to Japan and seek recognition of a refugee status , there are various other forms of refugee acceptance, including government-led third country resettlement and residence permission under emergency evacuation measures of respective country of origins due to unrest circumstances.

With more than 100 million people forced to leave their homelands around the world, the situation where acceptance based on the Refugee Convention (go through application and Japanese government acknowledge to accept) alone could not cope, continues. It is a global trend in expanding the various forms of refugee acceptance, and it is also important as a mean of providing as many refugees as possible with a safe place to reside. However, in Japan, there are considerable differences in support depending on the form of acceptance.

Comparison of Government support for refugee applicants and Ukrainian evacuees

| Refugee applicants (Protection fees) | Ukrainian evacuees who could not find receiving countries | |

| Living expenses (1 day) | 1,600 yen | While residing in Temporary Accommodation Facility: 1,000 yen + meals After leaving Temporary Accommodation Facility: 2,400 yen |

| Housing support | ‧ Payment up to 60,000 yen per month (Single) ‧ No temporary assistance for Deposit and “Reikin” (Gratitude fee) OR ‧Move into Temporary Accommodation Facility (ESFRA) | ‧While residing in Temporary Accommodation Facility: Government provision ‧After leaving Temporary Accommodation Facility:Provision by accepting Municipality or Companies |

| Others | ‧Government will bear actual medical expenses as necessary ‧Limited admission to Temporary Accommodation Facility ‧Require time until payments made | ‧160,000 yen one sum payment when leaving Temporary Accommodation Facility ‧Medical expenses, Japanese language education expenses, etc. will be covered as necessary ‧Quick response for payment |

| Allowance | Protection fee amount*1 ‧FY 2021 (approx. 105 million yen ‧250 people) ‧FY 2022 (approx. 90 million yen ‧204 people) | Expenses related to contracting out support project for Ukrainian evacuees acceptance*2 ‧FY 2021 (approx. 520 million yen) ‧FY 2022 Reserve Fund (approx. 1.9 billion yen) usage decided No guarantor upon entry: 283 people Have guarantor upon entry: 2,220 people* (as of 9/20) *It is assumed that the guarantor will provide living support |

For example, let’s compare Japan’s refugee situation with Ukrainian evacuees who could not find receiving countries. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Japanese government, at its own accord, started accepting Ukrainian evacuees (283 people as of September 15, 2023) who could not find receiving countries22. As the table above shows, the government provides temporary accommodation facilities and living expenses after arrival in Japan. Generally, for refugee acceptance, it is believed that by providing sufficient support right after entering the country, a smooth transition towards independence can be achieved. Whether this support is sufficient and appropriate leaves room for debate; however, it can be said that such support IS necessary.

For refugee applicants, initial support is extremely limited. Far from providing support towards independence, the level of support is difficult to even maintain a basic standard of living.

Since each situation differs, it is not possible to easily categorize the situation and difficulties by nationality, but it is clear that the structure for accepting evacuees who left on their own (refugee applicants) is still weak. Regardless of the form, there must be a system in place for people who have sought protection in Japan to receive appropriate support after arriving in Japan and take the first step towards independence.

4. The ideal state for Japan in comparison to other countries

In this section, we introduce specific aspects of the public support systems for refugee applicants in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Sweden, of which Japan ought to refer to23. Japan has been criticized by the United Nations and the foreign media for its lack of refugee acceptance24. While all countries face challenges, there is a lot that we can learn from what other countries have achieved by actively accepting refugees and improving the system through trial and error.

The basic data indicates the number of refugee applicants and assistance recipients in each country. Please take note of the incommensurable differences in the number of assistance recipients to that of Japan’s. More specifically, we strive to learn from systems that ensure the refugees don’t end up homeless immediately after entering the country (applied to all countries below); temporary assistance given even before the formal provisions are decided so as to prevent gaps in the safety net (United Kingdom); allowing employment in the country if they anticipate a long waiting period until the refugee application results, so that refugees can avoid relying on assistance (France); and guaranteeing minimum life security regardless of their residential status in the country (Germany).

Each country’s public assistance data for refugee applicants

*Systems are regularly updated. Please refer to the primary information for the latest.

United Kingdom

Basic data

- 167,289 Refugee applicants (end of 2022)

- 117,450 Recipients of one or more of housing, food, and livelihood assistance (end of June 2023)

—

- The Home Office is responsible for refugee assistance in the UK under the Immigration and Asylum Act of 1999, mainly aiding based on section 98 and section 95.

- Section 95 outlines assistance for economically disadvantaged refugees, such as those who do not have safe housing. Free living facilities with food are provided and as of the end of June 2023, 106,607 refugees have received this assistance. They stay for approximately 3-4 weeks and if there is no opening, a hostel is provided. This assistance is available during the refugee application process and 28 days after acceptance or 21 days after rejection.

- Those that need assistance while waiting for their section 95 application results can apply for temporary emergency assistance through section 98. This is terminated immediately after section 95 is accepted. As of the end of June 2023, 6,735 refugees have received this assistance.

- Additionally, Section 96(2) can be offered if an individual examination deems it necessary to provide further assistance.

- Those whose refugee applications are taking over 1 year are permitted to apply for employment, albeit within limited job occupations. They can join the NHS system without paying insurance fees.

France

Basic data

- 142,940 Refugee applicants (end of 2022)

- 111,901 Recipients of livelihood assistance (end of 2021)

- 108,814 Recipients of housing (end of 2022)

—

- The French Office for Immigration and Integration (OFII) is responsible for refugee assistance in France, under the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigners and of the Right to Asylum.

- Livelihood and housing assistance is provided in the form of the Asylum Seeker’s Allowance (ADA). To apply for this allowance, the applicant must be over 18 years of age and earn less than the salary that makes you eligible for France’s public assistance and be in the process of the refugee application.

- Housing data is as follows. 49,242 stayed in accommodation facilities for asylum seekers (end of 2022) and 52,950 stayed in emergency accommodation facilities for asylum seekers (end of 2022).

- 6,622 stayed in facilities combining a detention center and administrative review (end of 2022).

- If OFPRA does not come to a decision within 6 months of the refugee application, the applicant can obtain employment and receive job training.

- In principle, refugees can retroactively receive all benefits (excluding public assistance) and social welfare from the day they arrive in France.

- The country’s health insurance, Puma or CSS, is provided to refugees according to their income status.

Germany

Basic data

- 261,019 Refugee applicants (end of 2022)

- 399,000 Recipients of livelihood assistance (end of 2021)

- 398,585 Recipients of housing (end of 2021)

—

- The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) is responsible for refugee assistance in Germany, under the Federal Social Assistance Law amongst others, and the Constitution guarantees the right to seek for asylum.

- The Federal Social Assistance Law (1961) allows refugees to receive minimum living security irrespective of their residential status.

- In principle, refugees stay in living facilities provided by the government while they wait for their refugee application results.

- For 18 months after submitting the refugee application, refugees are required to stay at an Inicial Reception Center where 3 meals are provided each day. After that period, refugees will move to facilities managed by the local government or NGOs.

- Employment is not permitted whilst staying at an Initial Reception Center. However, employment is permitted if the refugee holds a residence permit and 9 months have passed at the Initial Reception Center (excludes “persons from safe third country”).

- Refugee applicants can receive 75~82% of the general social security allowance.

Sweden

Basic data

- 14,469 Refugee applicants (end of 2022)

- 8,542 Recipients of livelihood assistance (end of 2022)

—

- The Swedish Migration Agency is responsible for refugee assistance in Sweden, under the Law on the Reception of Asylum Seekers (LMA).

- Refugee applicants can stay at government or private facilities. Single refugees share rooms, but special considerations can be made for sexual minorities.

- Livelihood assistance for refugees is 46% of what is given to the general public.

- Application for employment can be submitted immediately after the refugee application.

- Medical fees are reduced, and if it exceeds 400 Krona (approx. 5,200 yen) in half a month, assistance is provided.

5. Lastly: Respect and Safety for Refugee Applicants

For refugee applicants, the daily stress of waiting for a response on their protection fee application while relying on the limited support provided by JAR is considerable. Even those who were initially motivated to study Japanese find themselves physically and mentally deteriorated due to the uncertainty and instability of their lives.

A refugee applicant said:

“When I arrived in Japan, I was relieved that my life would be saved. However, I never imagined that I would be pushed to the brink of becoming homeless in peaceful Japan. I can’t work right now, so I can’t live without support. But I don’t wish to live off someone’s support. It pains me to ask for support. I want to live independently as a person.”

Regardless of nationality or residential status, one must live day-to-day as they wait for the results regarding their refugee application in Japan. There is no legitimate reason to deprive the right to live for those who have reason not to return to their home country, and exclude them from society. There is no disadvantage to our society by providing the appropriate support, allowing those who can work to have employment opportunities, and live independently while waiting for the results of their refugee applications.

JAR will continue to push the government to recognize the Hogohi, the only public assistance available for refugee applicants, as a right instead of a benefit, and take responsibility to guarantee that right, regardless of nationality or residential status to allow refugee applicants to live with dignity as a “human being”.

- All content regarding the situation of refugees in this article are based on information and knowledge obtained by JAR through its support activities.[↩]

- RHQ, “Support program for refugee applicants” https://www.rhq.gr.jp/support-program/p05/[↩]

- However, refugee applicants without residential status or work permits (such as those on provisional release) are in a situation where they cannot expect to become independent through employment. Therefore, some applicants continue to receive the protection fee while they await response for their refugee application.[↩]

- The Refugee Applicant Protection Guidelines (p.20) states “income exceeding a calculated standard amount, coming from a stable job or remittance from family” as one of the reasons for termination of protection.[↩]

- The sum of the approximately 33.3 months from the 1st review and the approximately 13.3 months from the 2nd review (appeal.) Immigration Services Agency “Number of recognized refugees in 2022” https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/publications/press/07_00035.html[↩]

- Japan Association for Refugees “Comments on the Ministry of Justice’s announcement “Further review for optimizing the refugee recognition system””

https://www.refugee.or.jp/report/refugee/2018/01/post_456/[↩] - The term “foreigners” in this article refers to foreign nationals (including stateless persons) staying and settled in Japan for a certain period, and not those on short term stay such as sightseeing. Furthermore, although this article focuses on refugee applicants, it is also important to address the issue of guaranteeing the right of life of foreign nationals living as a member of Japanese society as *foreigners.”

For more information see “Guidebook for Guaranteeing the Right to Survival of Foreigners” (Akashi Publishing, 2022[↩] - In the European Union (EU), it is a requirement to ensure that refugee applicants have a dignified standard of living equivalent to nationals of the treaty member countries.

In the first place, refugees do not become “refugees” only when recognized as such by a country. Refugees are recognized as refugees because they are refugees, and it is important to understand that they need protection during the application process. For more information on “refugee recognition” see https://www.unhcr.org/jp/rsd[↩] - Administrative Management Agency, “Recommendations based on the results of the refugee administrative inspection” 1982[↩]

- Refugee Support Association “5th Refugee “Protection Fee Cut” and Emergency Campaign+ A Society Driven by Citizens” https://www.refugee.or.jp/10th/105h5/[↩]

- National Conference on Welfare Protection Issues (2022) “Guidebook for Guaranteeing the Right to Survival of Foreigners” Akashi Publishing, p31-33[↩]

- Japan Lawyers Network for Refugees, 2015-2023 Statement of Questions by Representative Michihiro Ishibashi http://www.jlnr.jp/legislative/index.html[↩]

- In the case of receiving living expenses (1,600 yen / day, or 1,200 yen /day for those under 12 years old) for 30 days.

A single person receives 1,600 yen×30days=48,000. A family of 4 receives, (1,600×2+1,200×2) ×30 days=168,000.[↩] - In April 2023, the “Refugee Forum (FRJ),” a refugee support network organization which JAR is a member, successfully raised the upper limit on rent from 40,000 yen to 60,000 yen (for a single person) through negotiations with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[↩]

- Reapplicants who are going through a trial (first trial only) regarding the disapproval of their first application are eligible to receive the benefit. Restrictions began in April 2010 in response to the budget depletion that occurred in 2008 – 2009.

(Reference) April 1, 2010, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs Division Director’s Notice “Review of protective measures for refugee applicants in poverty*[↩] - Of the 377 people who were recognized as refugees between 2010 and 2021, approximately 7% (25 people) were reapplicants.[↩]

- Because the year of applying for refugee recognition and the year of receiving the protection fee do not necessarily match, and that statistics are captured in different periods (January to December for number of refugee applications, and April to March for protection fees), the percentage of protection fee recipients are only for reference.[↩]

- The number of protection fee applicants and the number of recipients of the protection fee are as follows. However, the receiving rate is unknown since the results of the application may be returned within the same year of application.

FY2022: 221 applicants, 204 received

FY2021: 148 applicants, 250 received

FY2020: 311 applicants, 357 received

FY2019: 574 applicants, 362 received (unit: people)

(Source) Question letter written by Representative Michihiro Ishibashi http://www.jlnr.jp/legislative/index.html[↩] - The reality seems that the government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) does not hold specific housing units, but instead works with private real estate companies and support groups to secure vacant rooms according to needs. https://www.rhq.gr.jp/support-program/p05/[↩]

- Nobuo Teramoto, UNHCR NEWS NO.32, “Current status and challenges of Emergency Shelter for Refugee Applicants (ESFRA),” 2005, p7.

https://www.unhcr.org/jp/unhcr_news[↩] - Japan Lawyers Network for Refugees, 2016 Statement of Questions by Representative Michihiro Ishibashi http://www.jlnr.jp/legislative/index.html[↩]

- Immigration Services Agency “Regarding the status of accepting and supporting Ukrainian refugees”

https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/001388292.pdf[↩] - The information presented here is based on an internet survey and is not based on a fact-finding survey. It is assumed in fact there will be differences between the system and the reality.

The system is periodically updated, and the information is on current as of the update. In addition, because the situation in each country is different regarding social security systems available for anyone regardless of nationality on top of public assistance provided to refugee applicants, it is not the purpose of this article to weigh the strengths and weakness among different systems.[↩] - Refugee Studies Forum “List of recommendations to the Japanese government regarding refugees, detention, and repatriation”

https://refugeestudies.jp/2022/11/post-5084/[↩]